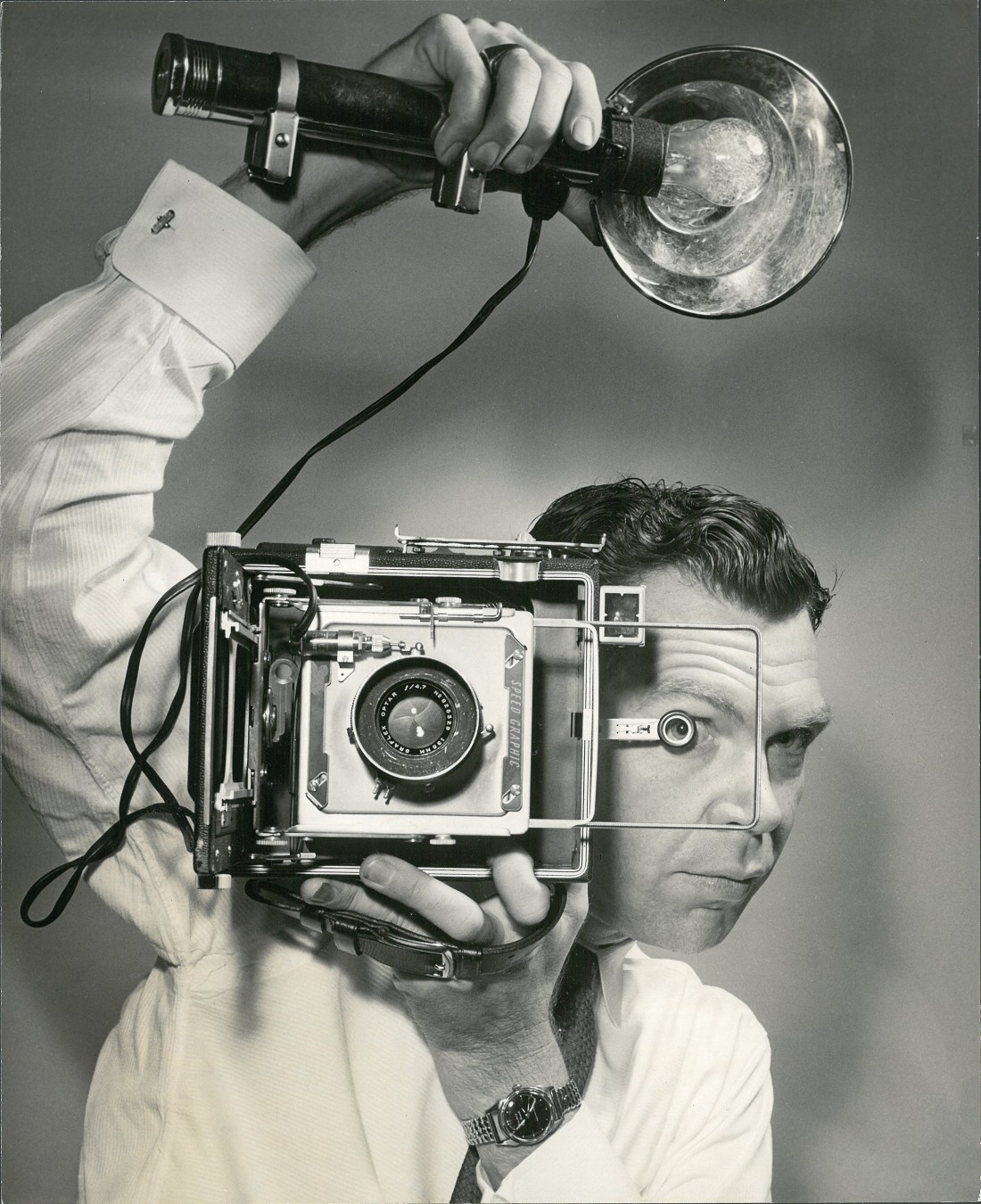

Mind’s Eye: Bob Williams

About this series: Memphis has played muse over the years to artists across the spectrum, from the music of Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley, Al Green, and the collective at Stax Records, to the prose of Peter Taylor, Shelby Foote, and John Grisham. But what about visually? The look of Memphis has been described equally as gritty, dirty, active, eerie, beautiful, and captivating.

In this series, titled “The Mind’s Eye,” Memphis magazine will be taking a closer look at some of this city’s most prominent photographers, a few homegrown, many transplanted, but all drawn in by that grittiness, that activity, that beauty.

Is there something special about the look of Memphis? We’ll ask each and, along the way, learn what makes these photographers tick, what got them started on their professional paths, and what it is that keeps them looking around every corner and down every alley. We’ll turn the camera on the cameramen, as it were, capturing their portraits and seeing what develops.

At the same time, we will be showcasing each photographer’s own remarkable work. Hopefully, that will speak for itself.

— Richard J. Alley

In his small office at his home in Kirby Pines Retirement Community, Bob Williams, 91, is surrounded at every turn by photos, most of which were taken by him. A photojournalist for The Commercial Appealfor 33 years, Williams retired in 1982 as the newspaper’s first photo editor. He’ll point out award-winning photos, sentimental favorites, and name off his children and grandchildren, his favorite models over the years. But there is something else in his work — his time as a photojournalist represents, not just an impressive, single-minded career the likes of which are rarely seen these days, but because of the nature of his work, it is a time capsule of Memphis history.

His original fascination with photography came as a child and through a scoutmaster who taught a young Williams how to develop film. “You just can’t imagine, here you are with a negative, and then you take it and you make a contact print the same size as the negative, or you can put it in an enlarger and blow it up,” he says. “It was just magical and it grabbed my interest.” A Kodak Brownie box camera belonging to his mother was his first camera. It’s among many vintage cameras Williams still owns.

He learned more about the craft as an apprentice to a photographer who rented space from his mother in a commercial building she owned in downtown Amite City, Louisiana, where the family lived.

An incident as a teenager would cement his faith in God and strengthen his ability to live in the moment, a useful trait for any good photographer. As a tornado destroyed his home, the 17- year-old was miles away in Hammond, Louisiana, having hitchhiked there with friends looking for adventure. His mother and two brothers were in the house, but were miraculously spared. “I was protected because of doing something I’d never done before in my life,” he says. “I left home without anybody knowing. When I did get home, [I found] a pecan tree had fallen across my bed, and that’s where I would have been; I would’ve been gone. My whole family was saved.”

As a result of that destruction, Williams and his family moved to Memphis in 1941, where his background in photography led him to shooting portraits at Reynolds Studio in the Deluxe Arcade on Madison Avenue at Second Street. His only formal training would come during his time in the service with the Air Force photography school at Lowry Air Force Base in Denver.

Williams was in a liaison outfit that traveled overseas to Casablanca and Oran in North Africa, up to the island of Corsica, and to Italy, shooting photos for historical and military purposes. Once the war in Europe ended, his group was given immediate orders to go to Okinawa in the Pacific, and he turned 21 while at sea. After the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, the ship he was on, the S.S. Sea Owl, was ordered to change course and return to Boston. “We were the first troopship to land in the States after the war was over,” he says.

He was in the service for three years before he returned to Memphis and, he says, “I had so much photography under my belt, it would have been ridiculous to change professions.”

He was hired at 24 years old by editor Frank Ahlgren of The Commercial Appeal in 1948 to replace a photographer who had gone to work for the first television station in town.

“My life had been sort of a shambles up until the point I went to work for the paper,” he says, “and I made up my mind right then that this is what I’m going to do for the rest of my life, and I’m going to tackle it with all of the vigor I have and make something of myself.”

It was a different time, to be sure. The daily paper of record was a living, breathing machine, churning out features and spot news the way the former automobile plant it operated in had churned out Fords. There were four photographers on staff covering a city that extended east only as far as Highland Avenue. The darkroom facilities, he says, were abysmal. He was told by Ahlgren that the newspaper business wasn’t a well-paying industry, and to compensate he should feel free to use the facilities and materials for any outside, freelance work, as well as to sell prints he’d made for the newspaper.

“The harder you worked, the more money you’d make,” he says. “They didn’t realize how much; they gave me a license to steal.”

His newspaper photographs acted as advertisements, eliciting calls from organizations and individuals needing quality photos, from marketing and advertising agencies to family portraits. He took that money made from his freelance work and began buying up real estate, at one point owning 14 rental homes and apartments around town.

Photography has been an important element in Williams’ life. Not just for the career it’s given him, but for the life and family. As a professional photographer, Williams was once asked by a photography student to critique his work. Williams did, begrudgingly, and was mesmerized by a small photo of a young woman the man had taken. The image stayed with him and the next day when his boss mentioned a dogwood tree in full bloom on Belvedere in Midtown that would make a good photo for the paper, Williams went on the hunt to find this young woman to model in front of the tree. He tracked her down, she agreed, and they got the picture. He asked her out to dinner while they awaited the 9 p.m. early edition, so she could see herself in the newspaper and they hit it off. He married Jo Pulliam a year later and the two have been together for 61 years, with three children — David, president and CEO of Leadership Memphis; Kristin Ammons, who, with her husband Doug, owns the Shelby Forest General Store; and Paula Hartley, an advertising executive in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma — and four grandchildren.

Williams’ interests, and surely his reputation, lay in the human interest, feature pictures. “Anybody can take a camera and go to the scene of a wreck and get a couple of crumpled cars in a picture, or go to a fire and get a picture of the smoke coming out,” he says. “But feature pictures appeal to everybody.”

And nobody showcased human interest images better at that time than Life magazine. “They [Life] did everything so well, had so many good photographers they paid great salaries to,” he says, adding that the heralded publication once came knocking on his door. “They offered me a job for $50,000 a year when I wasn’t making but about $6,000 or $8,000 a year, and it was a great temptation, but I’d started my family by then, and I couldn’t afford to make the move. It was a great temptation and the dream of every photographer, but I had to turn it down.”

Yet he would soon see his images in those pages. Long before there was Flickr or Instagram or any other photo sharing, social media networks, Williams took a daily photograph of his son for a year beginning when the boy, born at St. Joseph Hospital, was only four minutes old. These days, “365 photos” projects are ubiquitous among novice photographers who need a prompt to snap a picture. Williams needed no prompt, the camera was always at hand, and he was always ready to capture what he saw. He took a picture of David every day just after he was born. “Pretty soon we had three months of pictures done and I said, ‘Let’s go for a year.’”

At the end of the year, Williams called the Life photo editor and told him about the project; the editor asked to see them. In the era before zip files or Dropbox, Williams snail-mailed those prints to New York. “When he got them, he called me back and said, ‘There’s not a wall in New York big enough to mount 365 8-by-10s.” Williams sent the negatives and someone at Life had to reprint them. The layout appeared in the magazine on November 22, 1954.

Despite his love for the story-telling features, Williams also shot the hard news of the day with an eye for how the heart and scope of a picture might convey the import of an event. What he caught through his viewfinder was history in the making. He was working the photo desk the night of April 4, 1968. Realizing he was closer to the Lorraine Motel than anyone, he grabbed his own camera and headed out the door, snapping pictures of the ambulance carrying King as it sped away from the scene, and of James Earl Ray’s perspective from the bathroom window of the rooming house from where he’d fired the shot. These were images that would be shared throughout the country in the days following the tragic event.

Earlier, Williams was granted front-row access during the Emmett Till murder trial in 1955, capturing defendants and their wives talking at leisure while they awaited the jury’s return with a not-guilty verdict.

There are photos from the University of Mississippi as well, and James Meredith being escorted to class by guard as he integrated that school in 1962. An aerial view shows U.S. Army trucks blocking Oxford Square in the wake of protests.

And there are lighter moments spent with Elvis Presley, who befriended Williams and granted him wide access. Then there are the photos of the spectacle that ensued when a 400-pound black bear showed up on a rooftop on Park Avenue, later captured and taken to the Overton Park Zoo.

Williams’ advice for aspiring photojournalists: “First thing you do when you arrive at a scene is make a picture immediately, because you don’t know when you’re going to get run off or what’s going to happen. As long as you’ve got one in your pocket, you feel safe, and then you start trying to improve it and do a better job.”

Williams spent the last 14 years of his career with The Commercial Appeal as photo editor before retiring. In his duties as editor, he was off the streets and, he says, “I enjoyed making pictures, but I didn’t want to demote myself.” So after retiring, he went to work for five years for the Baptist Hospital system as a staff photographer.

At 91 years old, Williams is still sharp. Flipping through a large album of his prints from the middle of the last century is like touring the man’s mind. Pictures elicit memories, and he shares details of how a photo came to be, or points out where the eye should go. For Williams, there should always be a single point of interest. This isn’t basic composition, but the heart of a photo, the emotion buried within a detail that connects it to a viewer. “Everybody loves to be entertained,” he says, “so I tried to build my career around that.”

Click here to go to the Memphis magazine site and view more photos from Bob Williams.