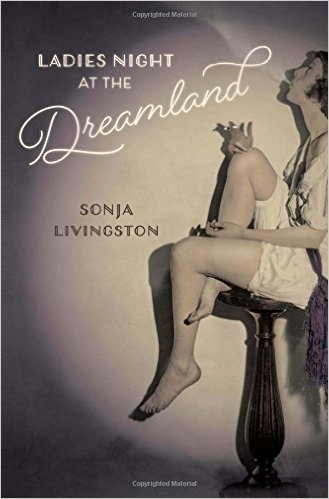

Dreamland

I’m somebody who’s more timid than I want to be,” says Sonja Livingston, associate professor in the M.F.A. program at the University of Memphis.

That’s the beauty of literature: The ability to lose yourself in a book and live many lives, to experience adventures that take the reader around the globe, to outer space, and into situations impractical in the day-to-day of our real world. And for writers, it’s the thrill of creating these worlds, of embellishing our domestic escapades into something larger than life.

Livingston, though, is a memoirist and, as such, trades in truth and facts. But there’s always wiggle room, isn’t there? And in the genre of literary nonfiction, a vivid imagination is as essential as a library full of reference books. Her latest book, Ladies Night at the Dreamland (The University of Georgia Press), is “a group of essays inspired by women I never knew but wanted to know,” she says.

The essays blur the line of fiction and reality, and in doing so, Livingston is able to explore the courageous and stare fear in the face. “I noticed that the women I was mostly interested in tended to be those who lived outside of the lines,” she says. “I’m interested in all lives, I’m curious about humans; but women especially, I think, have been quiet about their stories. So as I learned about these various lives, I found myself thinking about each of the characters and wanted to know a little bit more and wanted to know what I could learn, maybe, about myself through them.”

“The Opposite of Fear” is the story of Maria Spelterini, a young woman who crossed Niagara Falls on a tightrope in 1876. At the time, such an activity was all the rage: In 1859, The Great Blondin crossed; and a year later Signor Farini followed. A series of copycats would walk their way through the mist until “the regularity of their stunts and their relatively easy success caused crowds to weary of the tightrope walkers,” Livingston writes. “But a woman. Well, a woman in a short skirt defying death was a different matter altogether.”

Farini shows up again in the essay “Human Curiosity,” the “father” and exploiter of Krao, a 7-year-old girl presumably “rescued from the monkey-people of Burma” or “stolen from the jungles of Siam.” She is put on display as a novelty, a sideshow act in the 1880s, billed as Darwin’s missing link. At her funeral, respects are paid by the Giant from Texas, the Fat Lady, the Leopard-Skin Girl, sword swallowers, and “ladies with tattoos blooming on the trellises of their flesh.”

The structures of the essays vary, as do the time periods. Vary greatly, in fact, from the turn of the last century to present day. Livingston’s use of language is sparse like Michael Ondaatje writing about the birth of jazz in Coming Through Slaughter, or his own family’s mythology in Running in the Family. The result is a work of nonfiction that reads like fiction as she tip-toes across the narrow divide separating the two like a Spelterini with a laptop. The stage is set for what she’s about to attempt early in the opening pages: “ …the Dreamland belongs to the past, except as it exists in these pages. And even here it’s a passing fancy — its wood floor and bandstand — constructed of memory and imagination to hold the girls and women in this collection.”

The stories pass through a brain attuned to facts and dates and the ease with which they can be accessed these days, but the language is poetic and it is this poetry that the brain truly craves. “Straight nonfiction isn’t necessarily literature,” she says. “It’s more about the content than the style, and literary nonfiction is a lot more about the style; content is important but not as much. So literary essays can be poetic, they can be personal, they can be all kinds of things, and I think this particular collection pushes a little bit further than I’ve ever done before in terms of being more literary and blurring that line.”

Her first encounter with the genre was Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, though she didn’t realize at the time that literary nonfiction was what she was reading. She took her first writing workshop on the creative essay because a friend told her she’d love it — and she did — yet she thought at the time, “What the hell is this?”

“That’s really where things cracked wide open for me,” she says. “I discovered lots of other writers and lots of possibilities, people who were writing these poetic, imaginative pieces.”

There is research involved, but, she says, it mainly involves reading books and the advantage for a literary nonfiction author is that those books are already written. She does travel to locations to see what a character might have seen, might have felt or smelled, saying, “I think sometimes I do things like that because it’s a way of knowing a place better.”

For “Mad Love: The Ballad of Fred and Allie,” Livingston drove out to Bolivar to lay eyes on the asylum where Alice Mitchell spent the rest of her life for the murder of her lover, Freda Ward, on the cobblestones beneath the Memphis Customs House in 1892. Both of those women are interred at Elmwood Cemetery, and Livingston has spent time there as well, walking among the markers and statuary, a resting place for, not only the dead, but other stories that might grab her fancy.

“I suppose I selected these women because they were also unusual and, in their own way, really sort of bold,” she says. “Even Alice Mitchell, it was a horrible crime, but that was a wild thing to do, to kill somebody in broad daylight. Not living the typical life is very appealing to me.”

In many cases there is so little known about a subject that what we come away with is more of a sense of the person than any hard facts. But that’s okay, it’s like the memory of a childhood best friend with only the most fun, exciting, and nostalgic bits at the forefront. Imagination is the greatest tool at her disposal as in the essay “Dare” about Virginia Dare, the first English baby to be born in America. That child, along with the entire lost colony of Roanoke, is a mystery today. So what can truly be known? “I don’t know anything about her except that nobody knows anything about her,” Livingston says, “so I really play with imagination a lot there.”

Livingston grew up in the Buffalo and Rochester area of Western New York. She is one of seven children raised by a single mother in a situation she refers to as “sketchy,” living a nomadic life without much money or many resources. She began collecting the memories of her childhood, one that she says was fun, but not at all stable. From that, though, bloomed her curiosity. “I think the way that it influenced my selection is I am interested in hidden lives,” she says. “We don’t tend to think of people growing up in the 1970s in New York State as living that way, as living on an Indian reservation or having an outhouse, so I was always interested in showing in my writing the lives that are little understood.”

She read a lot growing up — “Nancy Drew and whatever letters of the encyclopedia we could afford” — and, though a good student, she didn’t hit her stride until college, earning an M.S.Ed. from SUNY Brockport and an M.F.A. from the University of New Orleans. It was later that full-time writing became a part of her life. “Right before I turned 30, I started taking writing workshops and really loving it, and also finding out that the essay could be creative, that the essay didn’t have to be the form that we learned in high school with the introductory paragraph and all of that,” she says. “It could be that, but there was this other element and I could use some of the elements of poetry.”

While working as a school counselor in Rochester, Livingston received a call saying there was an opening for a visiting professorship at the University of Memphis. Her first book, the memoirGhostbread, had just been published and she was being asked to do readings and make public appearances to promote it. “It was becoming too much and I was going to have to decide, and so that opening just came at the right time.”

That was six years ago, and ever since first coming to Memphis she’s come to think of it as home. “I love Memphis — the music, the history, even the grittiness,” she says. “Every place has history, but I find this history especially rich and important to the whole nation. What’s happened here matters a whole lot.”

In “The Opposite of Fear,” Livingston lists the amulets and baubles she collects to aid her in the fight against her timidity, to bolster her courage in everyday life. “I’ve tried to cultivate many charms,” she writes, “how fine it would be to carry a source of protection, an object to embolden me.” They include worry dolls from Guatemala, a pewter Virgin Mary, and a South African coin. To that list could be added this collection of essays where we all can glean the courage it takes for the young women chronicled to make it through lives that are, many times, less than ideal, or to help us realize dreams that might, in our daily routines, seem just out of reach.