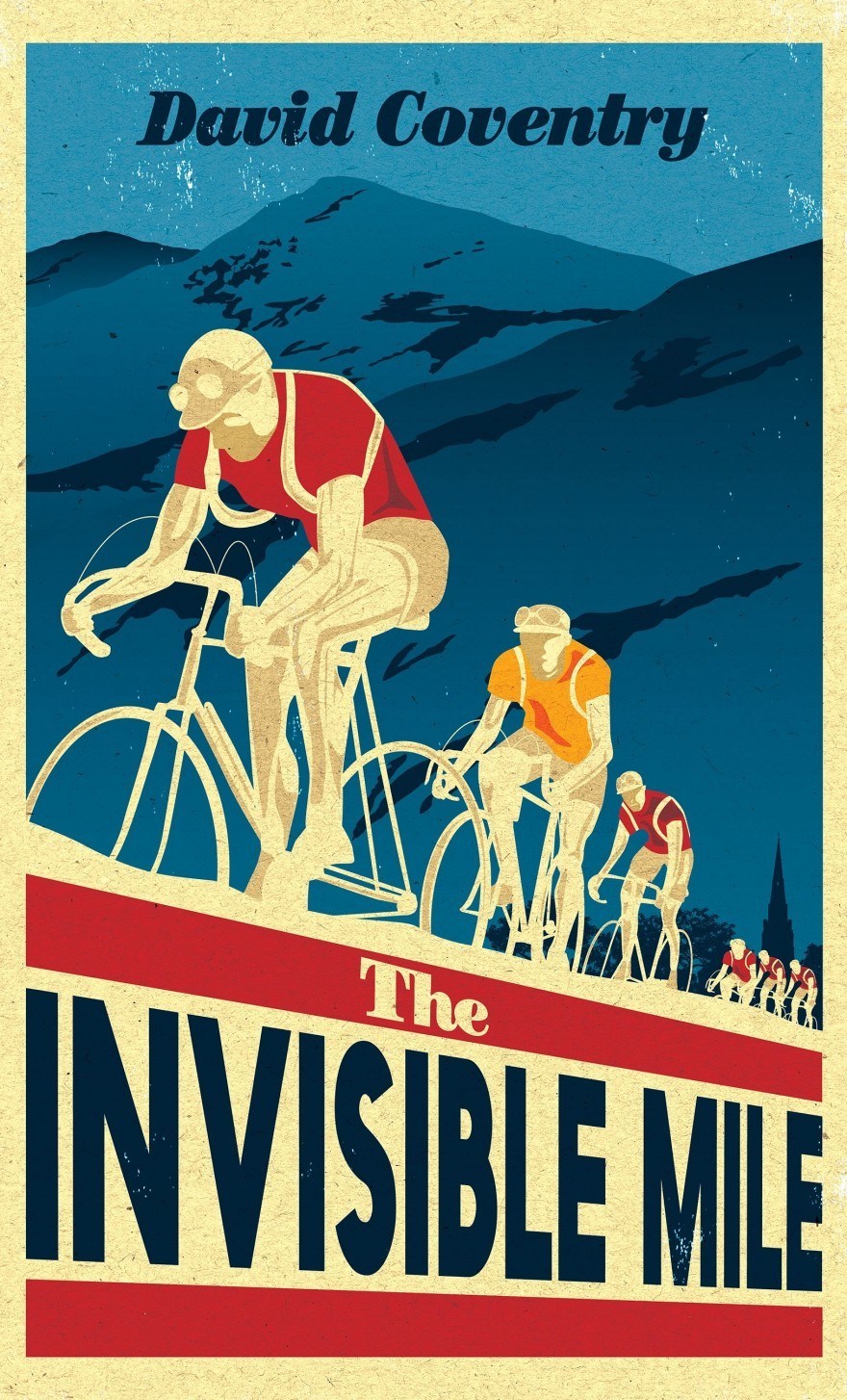

The Invisible Mile

If you’re like me, around the time Memphis social media was blowing up over news that Zach Randolph would be wrapping his dishes in newspaper in preparation for a move west last July, you were caught up in the drama of super-sprinter Peter Sagan’s disqualification from this year’s Tour de France following his fracas in Stage 4 of the race.

I know, I’m still upset about it, too.

My schedule over those weeks was simple: watch the present-day Tour coverage live in the morning, followed by reading The Invisible Mile (Picador), David Coventry’s novel set during the 1928 race, at night.

Through the eyes of a domestique, the youngest rider on the team, we witness the unveiling, mile by mile, of the Ravat-Wonder cycling team of New Zealand/Australia, the first English-speaking team allowed in the storied race begun in 1903. (I’m sure you caught that there — it’s a 1928 Australian team, and Sagan has been accused of knocking Mark Cavendish, an Australian, from his ride during a final sprint in 2017. It’s uncanny.)

Along the way, the young rider carries in his panniers memories of home and a sister whose fate we learn along the journey. His memories of the first World War, too, become vivid with each revolution of his machine’s gears.

While a fan of the race, I was unfamiliar with some of the names from the past as the announcers of today’s Tour de France rarely take us back beyond the career of Eddy Merckx. So as I read, I made frequent pit stops on Google to learn how easily truth can draft in behind such elegant lies. There was indeed an Australian/New Zealand team first introduced to the 1928 Tour de France, and it was led by Hubert Opperman and Harry Watson, just as in the novel. Other characters such as Camille Van de Casteele were actual participants as well.

The Invisible Mile is a long look at the Tour de France in its infancy. Today’s participants ride from one day’s finish to the next day’s start aboard luxury motor coaches with masseuses, team doctors, and personal chefs. Their gear is the most high-tech, up-to-date available and, in most cases, is designed for each rider. It is science on pedals. But aren’t most sports these days? Science in pads, science swinging a bat, science running a faster and faster mile.

The constant for professional athletes (for most, anyway, as the dollar sign is still the ultimate measure of a personal best) is heart. And the men of the earliest Tour de France had it in torrents as they trudged up the same mountains they do today — the Pyrenees, the Alps — on machines made of heavy steel, not feather-weight carbon fiber, while carrying their own spare tubes across their backs and bags full of gears to be changed out manually depending on ascent or descent. Once at the finish, they searched for lodging and for restaurants that were still open, as they may have finished a stage in darkness or in early morning. Coventry puts us in that mindset, taking us to the flat plains and rocky outcrops of France with poetry mingled into his peloton of prose to fit us on the saddle so we can see and feel the road ahead.

“I shouted at myself as I climbed,” Coventry writes. “My bones felt the terror of my muscles as they stretched and shrank. Trying to take me up and up, they seemed to bend to the effort. I say this, but we were barely pedalling. And it’s a heavy agony. I thought only to cry when we hit the snowline. The pain was exquisite and I could not comprehend how my body kept working me onwards. It was deep, it was everywhere, surrounding every part of me. I felt myself become damaged; I felt every muscle disintegrating, lungs and heart turning to bloody pulp in my chest. But I went on, and it’s not a case of knowing how, rather it is the case that we did.”